March 28, 2024

A Federal Discovery Rule Sleeper You Can Use: Rule 27, Fed. R. Civ. P.

You hosin' us, Mr. Hull?

Rule 27 of the U.S. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure is "Depositions to Perpetuate Testimony". It's not invoked that often. Subdivision (a) covers "Before an Action Is Filed":

(1) Petition. A person who wants to perpetuate testimony about any matter cognizable in a United States court may file a verified petition in the district court for the district where any expected adverse party resides. The petition must ask for an order authorizing the petitioner to depose the named persons in order to perpetuate their testimony. The petition must be titled in the petitioner's name and must show:

(A) that the petitioner expects to be a party to an action cognizable in a United States court but cannot presently bring it or cause it to be brought;

(B) the subject matter of the expected action and the petitioner's interest;

(C) the facts that the petitioner wants to establish by the proposed testimony and the reasons to perpetuate it;

(D) the names or a description of the persons whom the petitioner expects to be adverse parties and their addresses, so far as known; and

(E) the name, address, and expected substance of the testimony of each deponent.

(2) Notice and Service. At least 21 days before the hearing date, the petitioner must serve each expected adverse party with a copy of the petition and a notice stating the time and place of the hearing. The notice may be served either inside or outside the district or state in the manner provided in Rule 4. If that service cannot be made with reasonable diligence on an expected adverse party, the court may order service by publication or otherwise. The court must appoint an attorney to represent persons not served in the manner provided in Rule 4 and to cross-examine the deponent if an unserved person is not otherwise represented. If any expected adverse party is a minor or is incompetent, Rule 17(c) applies.

(3) Order and Examination. If satisfied that perpetuating the testimony may prevent a failure or delay of justice, the court must issue an order that designates or describes the persons whose depositions may be taken, specifies the subject matter of the examinations, and states whether the depositions will be taken orally or by written interrogatories. The depositions may then be taken under these rules, and the court may issue orders like those authorized by Rules 34 and 35. A reference in these rules to the court where an action is pending means, for purposes of this rule, the court where the petition for the deposition was filed.

(4) Using the Deposition. A deposition to perpetuate testimony may be used under Rule 32(a) in any later-filed district-court action involving the same subject matter if the deposition either was taken under these rules or, although not so taken, would be admissible in evidence in the courts of the state where it was taken.

And subdivision (c), equally as vague in some respects (but see the Committee Notes), states:

(c) Perpetuation by an Action. This rule does not limit a court's power to entertain an action to perpetuate testimony.

Again, Rule 27--and its many state counterparts--is not used that much. In non-federal cases, most states have some versions of Rule 27, with different case law on how you can take discovery before an action has been commenced. Valid reasons might be to preserve testimony which might "get away", e.g., a dying or homeless witness or a witness about to skip town with the money. Or (less commonly) to do a limited pre-suit evaluation of the merits. The state versions are worded very similarly to the federal rule; however, the case law on what you can actually do with the state counterparts of the rule vary widely from state to state. It's a bit vague, but good lawyers can use that to their advantage for clients when they see it in statutes, regulations and procedural rules.

One common concern with the rule: It will be used to harass and intimidate (read: "mess with people") rather than to perpetuate or preserve. Unfortunately, it is used that way. And some judges just don't at first like what they don't see that much. In 2010, one very good if elected North Carolina state judge in beautiful Durham, N.C., initially was increasingly aggravated that some godless bow-tied out-of-state city lawyer who tried to pick up his sultry 27-year-old law clerk named Zoey right in front of him was introducing him for the first time to the state's Rule 27. Judge Quaalude didn't know much about it. But no one seems to.

So you teach and sell His Honor or Her Honor. You're an officer of the court, right?

But go easy, check the cases on it--for obvious reasons, there are not many--and think it through. Local lawyers may not be much help; understandably, they often have rote, unthinking habits about their own procedural rules. Hey, we all do that--and we are missing a lot. (See Rule 56(d) for example.) Rule 27, done right, saves time and money. Downside: you might have to sell it to, or be creative with, the local state or federal judiciary. Or refresh the collective memory. Boomers do forget stuff.

(Image: D.E.K. Enterprises/Henry Gibson as Judge Brown, Boston Legal.)

Posted by JD Hull at 12:22 AM | Comments (0)

March 27, 2024

Holy Surprises & Saving Graces: Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 56(d).

Early-in-the-case Rule 56 motion. Note well-dressed Brit General Counsel taking a bullet.

Rule 56

(d) When Facts Are Unavailable to the Nonmovant. If a nonmovant shows by affidavit or declaration that, for specified reasons, it cannot present facts essential to justify its opposition, the court may:

(1) defer considering the motion or deny it;

(2) allow time to obtain affidavits or declarations or to take discovery; or

(3) issue any other appropriate order.

Trial lawyers, in-house counsel and law students know that Rule 56 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, or summary judgment, gives a litigant an opportunity to win on its claims or dispose of the opponent's claims relatively quickly and without trial. Accompanied by sworn affidavits, and most often discovery responses, a Rule 56 motion tries to show that there is no real dispute about key facts and that the movant is entitled to judgment under the law. If the trial court grants it, the movant wins on those claims.

But what if a summary judgment motion is brought against your client suddenly and early in the case and the local rules of the district court don't give you much time to develop and prepare an opposition? After all, Rule 56 lets a party who has brought a claim file for summary judgment after 20 days, and defendants can file "at any time".

It happens pretty frequently. Both plaintiffs and defendants make the motion early on. Defendants do it the most. No matter who moves early, or how it is eventually resolved by the district court, it's very disruptive. It will fluster even the most battle-hardened-been-there-seen-that GC or in-house counsel. It's an expensive little sideshow, too. Everyone in the responding camp hates life for a while.

Subdivision (d) of Rule 56, "When Facts Are Unavailable to the Nonmovant", provides a safeguard against premature grants of summary judgment. Some good lawyers seem either to not know about--or to not use--subdivision (d) of Rule 56. In short, you file your own motion and affidavit--there are weighty sanctions if you misuse the rule, so be careful--stating affidavits by persons with knowledge needed to oppose the motion are "not available", and stating why. (More senior lawyers may know this provision as Rule 56(f); it was re-lettered in the 2010 amendments to the federal rules.)

The federal district court can then (1) deny the request and make you oppose the motion, (2) refuse to grant the motion or do what you really want it to do: (3) grant a continuance so that you can develop facts and, better yet, take depositions or conduct other discovery. Granted, it's a rule that delays, but if used correctly, Rule 56(d) can give you the breathing room and time you need to develop the client's case--not to mention avoiding the granting of summary judgment.

Posted by JD Hull at 11:59 PM | Comments (0)

February 09, 2024

Storytelling for trial lawyers, writers and actual humans in 16 words.

Don't tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass.

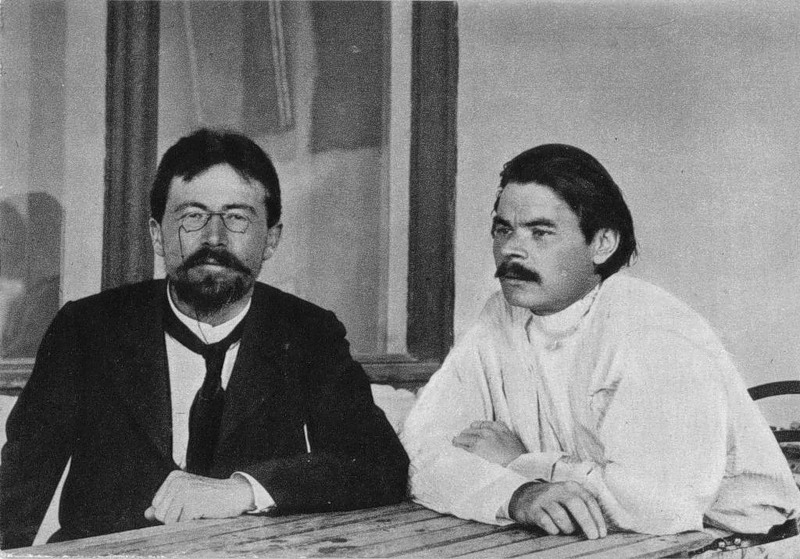

--Anton Chekhov (1860-1904)

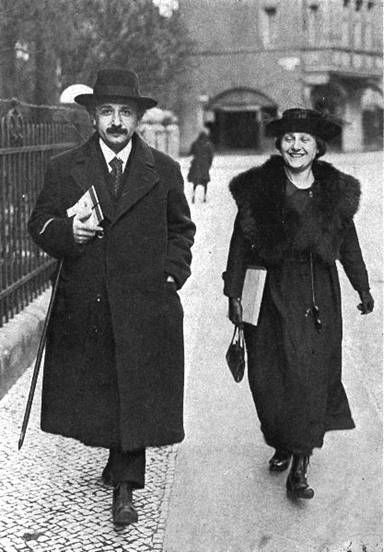

Chekhov with Maxim Gorky in Yalta, probably 1900

Posted by JD Hull at 10:59 AM | Comments (0)

August 04, 2023

Racehorse Haynes

I would have won them all if my clients hadn’t kept reloading and firing.

~ Richard Racehorse Haynes, 2009

Below: Haynes in 1979. War hero, Texan, trial legend, risk-taker and wit, Haynes died in 2017 at the age of 90.

Posted by JD Hull at 11:59 PM | Comments (0)

February 01, 2023

Sensitive Litigation Moment #631

Lawyering? A cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free, and good men die like dogs. And then there's a negative side.

--Holden Oliver, Salzburg, Austria

(3).jpg)

Posted by JD Hull at 12:58 AM | Comments (0)

January 27, 2023

REDUX: To Jurors, Does Your Staff Come Off Like Creeps, Weenies & Dorks?

It’s American trial season again. The period just after any holidays. Count on it most jurisdictions. But we now have fewer civil trials--in both American state trial courts and federal district courts--than we did fifty years ago. But we still have them. And lots of them have jurors. In America, we have so many different types of civil disputes in courts of record heard by juries that most Europeans, especially Germans, think we've gone a bit far with the right to a jury trial, and due process generally, if not completely around the proverbial bend. We waste too much time and money, some say. Maybe they're right. But under our federal and state systems, jurors are here to stay. We are dug in.

No matter how elitist or egalitarian you are on the subject of jurors here in the States, please understand something.

Jurors are not dumb. They miss little. They watch you and your team--lawyers, fact witnesses, expert witnesses, consultants, law firm employees and even partisan well-wishers you may have invited--in the courtroom, in the back of the courtroom, in hallways, in restrooms, in parking lots and in restaurants.

In short, they are watching you and yours. You get the idea.

Here's something you already know. Jurors will always surprise you in their decision-making. No matter what an expert might tell you, or how hard you've worked at selection, you're always wrong about one, two or three of them. You find out things about some of them at the verdict, with or without special interrogatories.

You'll learn tons more, however, if you have the opportunity to speak with them after the verdict comes in and they're dismissed. Ask them how they viewed the personalities in the courtroom and whether they formed opinions about anyone. Of course they did.

Creep Control

Anyway, during trial, don't go out of your way to antagonize jurors with sideshows which have nothing to do with the trial itself. Bring no "creeps" with you to trial. Keep them in the office. If they must show up--even for a moment--teach them to "un-creep" themselves, starting at 60 second intervals, and practicing until they can hold out for five minutes at a stretch. Hint: They pretend they are happy confident people who genuinely like other humans. And life. Breathe in. Breathe out. Repeat. And remember, you seek progress--not perfection. Be gentle at first.

Non-Creeps

Bring to trial no "non-creeps" capable of any snide, "mean" or creepy gesture, facial expression or body language glitch lasting more than one half-second. Instruct your non-creeps to read this post to be on the safe side. Reformed creeps--you spotted them early and sent them to rehab but they are ultimately powerless over they way they look or act--need pep talks, and brief courtroom appearances. See above.

Recovering Creeps Who Under Pressure of Trial May Relapse and Fold or Explode in Public

See above.

A Note on Nerds

In doses, however, a few generic dweebs and weenies running in and out of the courtroom with a huge box of documents, a phone message from your wife about Nantucket this summer with the Bloors, a good luck note from your mistress, your lucky bow-tie, your spats, your reserve pair of Bass Weejuns--face it, many on your staff are the kind of people you routinely made fun of in high school--is okay. Jurors expect nerds will be in the building. You're a lawyer. You live in a world where nerds are almost normal. Jurors get and tolerate that.

But jurors just don't like self-important "assisting creeps". That's really personal. Let us explain more.

A few years ago, after a two-and-a-half week trial, we won a jury defense verdict in a breach of contract and fraud trial involving three established companies and a super-nail biter which no one could call. Everyone had "bad" facts to deal with. All counsel and most witnesses did a fine job. An honest, fair, bright and even-tempered judge presided. So we interviewed some jurors right after the trial--and were told by all but one of them that they were seriously annoyed by some of the sneers, body language, guffaws and antics of the fire-breathing "let's kick some ass" associates and paralegals in the firms helping the plaintiff and the co-defendant in and out of the courtroom.

This seemed to happen a lot with two younger lawyers the same firm who sat together in the court room smirking and cockily approaching counsel's table bearing a note or message with an attitude that said: "take that" and "your sufferings will be legendary, chumps"--that kind of thing. Harmless macho stuff. But it hurt. Jurors noticed. In our interviews, some of the jurors used words like "creeps", "jerks" and worse to describe these people. The law firm's culprits were just over-jazzed, over-confident, over-macho and young (and they lost.) But their behavior, even subtle things, may have tipped the balance.

Don't screw up hard work and a client's chances at trial with mean-spirited sideshows confirming what many jurors thought about many lawyers anyway. Jurors are watching you, your attending GC, client representative and/or your witnesses and your associates and paralegals like hawks: in and out of session, in the halls, in the back of the courtroom, restrooms, parking lots, restaurants. Very little is missed.

Whether or not you think your trial people (men or women) are capable of looking or acting like "creeps" and robots of war at any moment during the roller-coaster ride of a trial, explain to them in advance the importance of "maintaining" a demeanor which appears professional yet fair, friendly, amiable and genuinely good-hearted. Better yet, hire only those people to help you present your case to a jury.

Note on other participants, witnesses, GCs: Wood-shedding of course is not soley for those smirking associates or nasty-ass paralegals who hate life. Plaintiffs, defendants, employees for both, fact witnesses and expert witnesses of parties need the same wood-shedding or cautionary harangue. In-house-counsel? No, generally not. They tend to get it.

Original post: January 6, 2012

Posted by JD Hull at 12:49 AM | Comments (0)

March 21, 2022

Sensitive Litigation Moment No. 114: In planning depositions, resist The Uninspired, The Lazy & The Half-Baked.

Do some common sense work before you take a deposition. And please don't squander the client's budget out of sheer laziness. You are paid to work on planning discovery, too. See this one.

"Do these guys ever think before they work?"

Posted by JD Hull at 12:59 AM | Comments (0)

January 17, 2021

Sensitive Litigation Moment No. 1: Crystal, the Missing Notary.

.jpg)

Crystal, blowing off work again--and just when you need her.

Not exciting. Just useful. In October of 1976, Congress passed a barely-noticed housekeeping addition to Title 28, the wide-ranging tome inside the U.S. Code governing federal courts, the Justice Department, jurisdiction, venue, procedure and, ultimately, virtually all types of evidence. 28 U.S.C. Section 1746 is curiously entitled "Unsworn declarations under penalty of perjury".

It allows a federal court affiant or witness to prepare and execute a "declaration"--in lieu of a conventional affidavit--and do that without appearing before a notary. Under Section 1746, the declaration has the same force and effect of a notarized affidavit. Read the 160 word provision--but in most cases it's simple. At a minimum, the witness at the conclusion of her statement needs to do this:

"I declare (or certify, verify, or state) under penalty of perjury that the foregoing is true and correct. Executed on (date). (Signature)”.

A "unsworn" declaration with the oath required by section 1746 can be used almost any time you need an affidavit, e.g., an affidavit supporting (or opposing) a summary judgment motion.

Some lawyers who practice in federal courts still don't know about the existence of Section 1746, (probably because so many of us practice primarily in state courts, and we stick to comfortable state practices and folkways). I wouldn't have known about it either; a Justice Department lawyer clued me in on it 20 years ago.

Federal judges understand and accept it. It saves clients, witnesses and lawyers the time, cost and aggravation of getting client statements notarized. Your three notaries--Nadine, Crystal and Raphael the Librarian, together with their notary kits--are in the office like clockwork, except, of course, the very days you need to have them witness and notarize a document. So it's a useful and convenient provision.

Not exciting--but it is one of the few efficient, and reliable, moments anyone sees in the trial process.

[Original WAC/P? post: February 3, 2009]

Posted by JD Hull at 08:31 PM | Comments (0)

May 18, 2020

Sensitive Litigation Moment No. 24: Is "Professionalism" a Convenient Dodge for Law Cattle?

Professionalism? What does it really mean?

So what about "professionalism". Is professionalism a vestige of an insular and ancient pageantry Western lawyers still engage in to feel special in an increasingly commoditized profession? Or does it have some utility?

Maybe the answer is both. But let's at least look at it freshly, and like people living in at least in the 18th century.

On closer inspection, real professionalism--generally thought of as a combination of day-to-day practical courtesies extended to fellow lawyers, and a noble tone in all that is said and done--may have little or nothing to with lawyers, and with benefiting lawyers. And have everything to do with clients, and benefiting clients instead.

Maybe the entire subject as traditionally regarded is either outdated, for lack of a better word, misplaced.

Shouldn't professionalism be 99% about clients? Some questions:

Original Post: September 4, 2011

(1) What is Professionalism in the field of law, anyway?

(2) When does it help the doing of work?

(3) Was it ever intended to benefit anyone but the client? (Sometimes, professionalism certainly benefits lawyers in a way that can greatly benefit, even if indirectly, their clients.)

(4) Do we lawyers cry "professionalism" in a way that conflicts with our clients' interests--or simply as a pretext, or dodge, to excuse themselves from doing their jobs at a higher level?

(5) If so, what can we do about that?

For some of the answers to these questions, see reprinted from a 2005 "Law Week edition" of The San Diego Daily Transcript, the article "Professionalism Revisited: What About The Client?". It ends with "rules of professionalism"--but from the client's perspective. Excerpts from Rules 1, 5 and 6:

1. We come first. Be nice--but if in doubt, use the rules. If you feel you know the lawyers you are dealing with, we will follow your advice and instincts. If you are in doubt about the lawyers, or if it might compromise us to deviate from the formal procedural rules, please stay close to those rules.

5. If you have, or would like to have, a personal relationship with opposing counsel, that's fine, but don't let the relationship hurt us--the client. We don't care as much as you do about your maintaining or developing collegiality with other lawyers in your jurisdiction; in fact, we could not care less.6. If opposing counsel shows animosity toward you for following the procedural rules and keeping things moving, that is tough. This is not about the lawyers. We hired you to represent us. We would like you to get this done. Again, as your client, we seldom think that aggression and persistence are "unprofessional".

Posted by Holden Oliver (Kitzbühel Desk) at 12:59 AM | Comments (2)

April 29, 2019

Discovery: Roll up your sleeves, folks. Trials are about People.

Trials are always about people.

Even high-stakes business v. business cases before federal trial courts or arbitrations panels abroad will lead your staff to an American Legion hall, a local official, a fire chief, or a beat reporter for a small newspaper.

Before you schedule a deposition, do some informal investigation. Next time a new case begins, resist rushing into written discovery and depositions. Step back from the discovery routine--you'll get into that bubble soon enough--and learn a few things on your own.

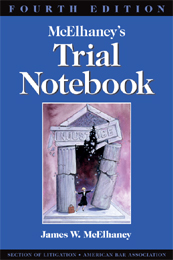

This is not a new idea. Over 20 years ago, James McElhaney, a gifted lawyer, writer and teacher of trial tactics, and the ABA Litigation Section, first published McElhaney's Trial Notebook, now in its fourth edition. Discovery, McElhaney noted, is a good way to learn what a witness will say, or to bind a party or witness to a particular version of the facts. But, he continued, it is also "a very inefficient way to get information."

Let us add to that:

Most of the formal discovery you see is worse than inefficient. It is often unimaginative, cookie-cutter, straight-up lazy, wasteful, client-unfriendly and a hopelessly dumb-ass way to learn much of the background information, and many of the facts, that will frame and flesh out your case. This is especially true of depositions, and (for that matter) any other live sworn testimony. If you really don't have to "wing it", don't.

So, hey, think a bit on your own. Prepare--but do that differently.

Each deposition should suggest a unique set of background questions you can have answered (or partially answered) before you begin. It's just a matter of curiosity and do-it-yourself "trolling" for information you and yours can get first-hand on your own. At a minimum, you'll have a better outline, a better deposition, and an adversary and deponent who knows you show up "ready to play".

Just as witnesses say unexpected and even startling things when they testify, useful and even surprising facts are available about opposing parties and witnesses through the Internet, court files, published cases, local boards and agencies, social clubs with websites, D&B reports, news archives, business libraries and even phone conversations other humans.

No, don't hire an investigator for this right away. You and your staff can handle this with a little verve and common sense, save money, and get steeped in the case.

It's fun. Roll up your sleeves. Un-weenie yourselves.

And why use deposition time to learn things you and yours can learn quickly and inexpensively and lash together from: phone calls, live humans, your client, client employees, ex-girlfriends, ex-husbands, ex-bosses, bartenders, town drunks, libraries, the Moose Lodge, store clerks, hopeless gossips, old dudes in cafes who drool on their shirts, neighborhood urchins, newspaper reporters--and even the most rudimentary Google search?

These inexpensive but ignored sources are often inconsistent with information parties will give about themselves in formal discovery.

The upshot?

1. Don't take the deposition at all. You may not need to take that deposition.

2. Take a much better and shorter one--and do much better written discovery requests. If you do take it, you will take a better one. You won't need to waste time asking about things which are easily ascertained beforehand. If you serve written discovery before depositions--you generally should do it before--your interrogatories and requests for documents under Rules 33, 34 and 45 will be much better. (Formal written discovery, in my view, is of even poorer quality and even less informed than most depositions taken.)

3. If you need to, confirm what you have learned with a quick series of leading questions. Anything that you have learned about the deponent from investigation and informal discovery, and that you need to confirm--i.e., work history, education, past events in the news, addresses, past titles, ex-employees, mistresses, ex-wives, published sonnets, tastes in biker bars, and current businesses and business associates? Go over it and confirm quickly at the outset (or at the right interval for that information) with the deponent.

Posted by JD Hull at 12:59 AM | Comments (0)

March 06, 2019

Jury Duty.

I could never be a judge. Wrong temperament. I’ll admit it.

But I do love being called for jury duty. This has happened in 3 cities up at the bench during jury selection, or voir dire:

ATTORNEY: Mr Hull, we know you’re a lawyer. Just one question. Can you listen to all the evidence and make a fair and reasoned decision?

ME: No.

Posted by JD Hull at 12:39 AM | Comments (0)

July 26, 2017

Winging It. Generally? Not Cool. No Bueno. No Bueno.

You've a talent for Winging It? Great. Congratulations. We will alert the media. Use that gift when you must. But please don't make it a procedure. Prepare.

.jpg)

Blarney Castle, Cork, Ireland

Posted by JD Hull at 12:52 AM | Comments (0)

January 05, 2016

On "lawyer professionalism", John Roberts, say it ain't so.

Lawyer professionalism is a morally pretentious, archaic, hypocritical and silly movement which [some bar communities] tend to invest in heavily to protect and coddle apathetic, mediocre and lazy lawyering. It keeps standards low, and the tone lawyer-centric. It is pro-lawyer, anti-client, prissy, routinely and dishonestly misused by incompetent and uncaring lawyers in defense of their delays and screw ups, and a waste of time and money.

--What About Clients?, December 2006

Like Bill Clinton, and although a bit younger and obviously a different breed of cat, SCOTUS Chief Justice John Roberts is "one of ours." He's a baby boomer--and other baby boomers are very proud of him. Me, too. He's my age, a fellow Midwestern corporate brat who attended law school in Boston with a number of people I knew growing up or have met along the way. We love to claim the guy.

He's a stud--and he certainly makes up for the rest of us boomers who will have on our gravestones this sign-off: "Brilliant, classically educated and still keeping my options open."

In his New Year's Eve state of the annual federal judiciary report, he made most of the right noises about the new and important if potentially troublesome "proportionality" amendments--troublesome, because I think the changes will be less intuitive and more difficult to apply for lawyers and judges than the Advisory Committee or your CLE instructors may have you thinking right now--to the discovery provisions of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. However, for reasons that aren't clear to me, this year Chief Justice Roberts also took up the "lawyer professionalism" cause, and it put the big hurt on my vision to have to read it:

As for the lawyers, most will readily agree—in the abstract—that they have an obligation to their clients, and to the justice system, to avoid antagonistic tactics, wasteful procedural maneuvers, and teetering brinksmanship. I cannot believe that many members of the bar went to law school because of a burning desire to spend their professional life wearing down opponents with creatively burdensome discovery requests or evading legitimate requests through dilatory tactics. The test for plaintiffs’ and defendants’ counsel alike is whether they will affirmatively search out cooperative solutions, chart a cost-effective course of litigation, and assume shared responsibility with opposing counsel to achieve just results.

In large part, John Roberts is talking about lawyer civility. Hey, no one has ever said that amicable lawyering in litigation is a bad thing. Like Motherhood and Good Crops, what's not to like? However, as we've said at this blog for over ten years, see e.g., Sensitive Litigation Moment No. 8: Is "Professionalism" Just A Lawyer-Centric Ruse?, and as I've been saying and writing for nearly twenty, "lawyer professionalism" is one of the most abused right-lawyering culture concepts in the history of the profession. It is the oldest anti-client "it's all about the lawyers" ruse going. It puts clients last and protects shoddy and dilatory lawyering. I'm really surprised the Chief Justice Roberts would sign his name to this ongoing scam, especially at a time when lawyer mediocrity is increasingly accepted and even coddled.

Like many great boomers, the guy knows how to sport a bow tie; I'll give him that.

Posted by JD Hull at 10:05 PM | Comments (0)

October 14, 2015

Sensitive Litigation Moment: The "C" word.

Pre-trial pro-trip for adepts. Some days lobbing the "C" word into brief chat about obvious differences between Rules 34 and 45 with a talented if lazy 35-year-old female opposing counsel plaintiff's lawyer gets more done than 10 Baby Boomers on Crack. Consult manual closely before attempting this.

Posted by JD Hull at 12:02 PM | Comments (0)

February 12, 2015

UPDATED: In federal trial court testimony, can you sneak your witness's religion into evidence? Do you want to?

My business litigation practice over the years has been chiefly in federal courts before one of our roughly 900 appointed federal judges. Trials get conducted under the straightforward federal procedural (FRCP) and evidence (FRE) rules. Only occasionally are my clients in state courts where in my experiences most jurists (1) are popularly elected, (2) openly provincial, (3) not overly-concerned with legal scholarship and (4) have their thumbs up their asses. Call me an elitist, a bomb-thrower or disrespectful but I'm fed up with judges who don't give a damn--and federal judges usually do give a damn.

Anyway, I've long thought that nearly all evidence/mention of person's religion or 'church life' has zero place in the courtroom. Interestingly, one longstanding general evidence rule in support of that idea is coming up a great deal more in the last 10 years or so. Rule 610 of the FRE is brief. "Religious Beliefs or Opinions: Evidence of a witness’s religious beliefs or opinions is not admissible to attack or support the witness’s credibility."

It's a good rule. A witness while testifying should not mention his or her faith or religion ("I'm a Baptist" or "I attend the Church of the Final Thunder) or say things like "I was talking the other day with [Pastor Joe/my Bible Study Group]" as it tends to suggest that the witness is more worthy of belief or a "good" person as a result of the connection to a religion. For purposes other than supporting or attacking credibility, a witness's religion or indicia of that religion ("I was in church when my ex-wife was blown away") can come in as evidence and regularly does. Religion, church and church life are still a big part of the lives of many.

It's interesting to think about. I learned this witness rule (i.e., FRE Rule 610) 25 years ago in law school. But it has been only in the past 10 years or so witnesses, often aided by their attorneys, seem to be trying to score brownie points with a judge or jury by sneaking their religious life into the proceedings. Why? I have no idea--except to speculate that with some populations in America religion or faith is a kind of moral merit badge people think they need to be socially accepted. That may be true, for instance, in certain parts of the American south, Appalachia and the Midwest. And, sure enough, that's where you see it the most.

In Ann Arbor, Michigan, Madison, Wisconsin, the northwestern states, and several California counties, on the other hand, religion may be much less important--and even a bad thing to some jurors. There is a growing chorus of respectable people all over the world who think that every religion as embraced by some is unproductive if not a form of mental illness. America contains a few geographic areas where groups of these "progressive" anti-religion people seem to live, too.

The way to keep this information out as an indicia of character or credibility? That's easier. You will probably first hear this kind of testimony in depositions before trial. If it comes up, you can file a motion to exclude (or motion in limine) under Rule 610 before trial for an order that this kind of testimony will not come in as evidence. Failing that, you can object to the testimony as it comes in, move to strike, and ask the judge to tell the jury that they must disregard the testimony. You may want to think carefully about how you do it if you do it in front of a jury.*

*My thanks to two fine trial attorneys, Oregon's David Sugerman and New York City's Eric Turkewitz, for a few if not all of the better ideas in this post.

.jpg)

Posted by JD Hull at 09:28 AM | Comments (0)

January 14, 2014

Sensitive Litigation Moment: Walken v. Hopper.

Posted by JD Hull at 11:51 PM | Comments (0)

December 20, 2013

Think like a client. The trick now is to win cheap.

For an experienced client, the cost of the lawsuit is part of the "victory" analysis. So is closure--or just getting it over with.

In America, the state and federal trial courts of record--rather than arbitration panels or mediation (which we Americans group together under the heading Alternative Dispute Resolution, or "ADR")--are still the "poison of choice" to resolve commercial disputes. That is likely to be true for a long time.

True, also, that our courts in the U.S. give even civil litigants (a) due process rights, (b) pre-trial access to the discovery of evidence, and (c) opportunities to present evidence at trial--each on a scale the world has never known before. While that "experience" is often tainted with inefficiencies and waste, it is at least predictable. Litigants generally accept the risks of what can happen to them--through flukes, brilliance, or the triumph of moral order in the universe--in American courts.

However, the "bad news" here is also considerable--and, of course, predictable. Business litigation in the courts is (a) extremely expensive, (b) highly disruptive to clients reps and witnesses, many of whom are managers or workers, and (c) very lengthy from start to finish. Even the "winning" client generally loses--and loses a lot in terms of resources and time.

However, our enduring global recession (or "new normal", perhaps) is certainly a good time for business clients to push for ADR (including mediation) over litigation. Not because ADR is cheaper, faster and better; often it's clearly not advantageous in any of those three ways.

It's simply because the cases you defend in struggling economic times can be more marginal from a merits standpoint. And that's exactly where ADR can really help. Even if you don't love ADR in America, or you were trained for full-blown trials.

Say you've just been handed a case to defend in an American court that is poorly-grounded, weak or otherwise insubstantial. A weak employment discrimination or wrongful discharge action (I call it the the "un-classy firing" suit). Or a flimsy business case dressed up as an unfair competition or infringement action (the "it's-weak-but-let's-see-what-happens" suit). Down-on-their-luck David & Son, with hungry counsel, v. Flatfooted Goliath, Inc., your client and a deep pocket.

The stars seem to be aligned in Goliath's favor.

Not only does your client Goliath have more resources, and the case filed against it is transparently contrived and weak, you are assigned to a real judge. Your firm is before a scholarly, honest, sane jurist with people sense, and loved by all. Your research suggests that the judge is business-savvy in rulings, and takes a dim view of iffy cases.

So you think you will win your case on a dispositive motion (and you do, eventually). You are right on the merits--and any law professor in the U.S. would agree with you. The "case" your long-time GC just handed you is silly, right? And a piece of cake. A cinch. Almost beneath you, you tell yourself. An "easy win", right?

Well, think again, Skippy.

Your GC couldn't have hired you to do anything more difficult. "Winning" just took on a new and more complicated meaning. Because now--especially if you were just handed a defense counsel's dream and stone "winner" of a case--you will have to work harder, and be smarter, than if you were defending a good faith or meritorious suit in which your client had the lion's share of bad facts.

The trick now is to win cheap*. An easy-to-win business suit handled by the most efficient defense counsel on earth can have defense fees and costs well over $100,000, even with minimal or no discovery. You really think that your GC or client rep will be happy the day you tell him or her about your great win on all counts based on your brilliant Rule 12(b)(6) or Rule 56 motion?

Don't bet on it. For the experienced client, the cost of the lawsuit is part of the "victory" analysis. So is "closure"--or just getting it over with. In a down American economy, litigation tends to increase. More suits are filed. And in my view clients and their plaintiff's lawyers file more questionable suits, i.e., ranging from Rule 11 violations and frivolous to iffy and wasteful. Employee and business nuisance cases are a big chunk of those filings.

A good arbitration panel or mediator will cut to the quality of the suit and its likelihood of success quicker than even the best American judges, who often feel obligated to give bad and iffy cases a wide berth. And good judges understand the problems of the business community and the utility of arbitration and mediation. Get jurists on your side in your attempt to drive iffy cases into ADR.

*Better to have "no lawsuit" than a great case or defense.

Posted by JD Hull at 12:00 AM | Comments (0)

December 10, 2013

CPR's Global Accelerated Arbitration Rules.

Choose to use them. They're aggressive and "get-it-done", in both letter and spirit. Global Rules For Accelerated Commercial Arbitration, of the CPR Institute. Best two features: (1) The default position is a sole (one) arbitrator. (2) Arbitrators should make award ASAP and in any event within six months of formation of the tribunal.

![CPRLogo[1].gif](http://www.whataboutclients.com/archives/CPRLogo[1].gif)

Posted by JD Hull at 11:59 PM | Comments (0)

October 11, 2013

Worship This: The Holy Surprise of a Child's First Look.

He was a loner with an intimate bond to humanity, a rebel who was suffused with reverence. An imaginative, impertinent patent clerk became the mind reader of the creator of the universe, the locksmith of mysteries of the atom and the universe.

--from Einstein: His Life and Universe (Simon & Schuster, 2007) by the Aspen Institute's Walter Isaacson, former Time managing editor.

Most of us are missing it all. --WAC/P?

"E" at the beach: Another fresh take.

Try this at home and work: The Holy Surprise of a Child's First Look. Forget for a moment, if you can, about Clients and Paris.

WAC/WAP? is at heart about Quality, Old Verities, and Values--the things no business, government, non-profit group, religion, politician or leader (a) wants to give you or (b) can give you. No, not even family and friends can.

You have to find them on your own. Work and Service, whether you are paid for them or not, are inseparable from these things.

At this blog, at our firm, and in our lives, we seek (in the largest sense) serious overachievers, and aficionados of life, past and present: identifying them, learning from them, having them as friends, hiring them and, above all, never holding them back.

It is often hard to find these people--or even to remember that they once existed.

We do, after all, live in a cookie-cutter world. Originality, intuition, authentic spirituality, and even taste are not valued--these traits are often feared and attacked--in most of the West.

This is especially true in America, where we continue to be geographically, culturally and (some think) cosmically isolated. The United States, despite its successes, high standard of living and exciting possibilities, has become world headquarters of both moral pretension and dumbing life down.

Besides, fresh thinking leads to painful recognitions. It's easier to let something else do the thinking for us.

"Fragmentation" is a word some people (including those with better credentials than the undersigned to write this) have used for decades to describe modern humans all over the world: lots of wonderful, intricate and even elegant pieces--but no whole.

So, in our search for coherence, we look for clues.

We look to television, advertising, and malls. To work, and to professional organizations. To secondary schools, universities, and any number of religions (none of the latter seem "special"--they say identical intuitive and common sense good things, but just say them differently), and to an array of other well-meaning institutions.

In fairness, all of these have their moments (hey, we all like our insular clubs).

And, importantly, we seek answers from others we know and love--family and friends--who have been soaked in the same messages and reveries, who make us feel comfortable with the same choices, values and lives that gnaw at us all in rare moments of clarity and solitude, and who are able to "reassure" us so we can get back "on track".

So what's missing?

It's Imagination.

Children come with Imagination. It's standard issue. Some lucky adults hold onto Imagination, even as it is bombarded with a tricky, confusing, and lob-sided mix of messages favoring mediocrity over quality. Until Imagination becomes a value in and of itself, a lot us will "shuffle off" life on earth without even knowing what happened in the past 80-odd years.

Elsa and "E" in 1920: They want you to think on your own.

We denied ourselves (a) thinking our own thoughts and (b) acting on our own. We would not even fight for these qualities. We would not take chances. We built, embraced and often defended a Cliff's Notes life. We were uninspired, desperate to fit in, and frightened. We "missed it".

We missed it All--like drunks who slept through the Super Bowl.

Our children, friends and people who respected and loved us even took notes on what we thought, said and did here as "spiritual beings" having a "human experience. They emulated us. That means you and me, Jack. How do you feel about that? Oh well. Next time, maybe?

Which brings us, finally, to Albert Einstein.

True, few of us can have Einstein's talent for Western logic, or his IQ. But Einstein's advantage over other physicists may have been that he was a "new soul". He looked at everything as if he were seeing it for the first time. Imagination.

Take work. He approached it from a wellspring of joy. There are, and have been, others like Einstein in that respect. Those are the kind of people we want as friends to inspire us, and as co-workers to solve clients' problems. His IQ and genius is not the point. We'll take an IQ a lot lower than Einstein's (for associates, though, Coif or Law Review would be nice).

Reverence and a child's awe. Imagination. That's the outlook we prize here at WAC? Energy, intensity and creativity always seem to come with it. If it comes with serious brains, we'll take that, too.

From past posts, and with grateful nods to Samuel John Hazo and Cleveland's Peter B. Friedman.

Posted by JD Hull at 11:00 PM | Comments (0)

February 24, 2012

Bongs at Work: Dude, the Doritos are key. Screw the due diligence. Service via Facebook.

At Reuters India, see "For Optimal Work Commitment, Skip the Pot?". It begins:

(Reuters Health) - According to a real shocker from the world of bona fide science, smoking marijuana is tied to less motivation at the office.

The author of the study said it can't prove whether that's due to the drug's effects, the social environment in which it's used or whether pot smokers are just more likely to be laid-back from the get-go.

Though researcher Christer Hyggen suspects pot is the culprit, another possible explanation is that people who aren't so happy with their work situation or motivated on the job are more likely turn to drugs.

"There's a popular belief that people who smoke cannabis are slackers and that they don't want to work," Hyggen, from the Oslo-based social research institute NOVA, told Reuters Health.

To see how well that perception held up, he analyzed data from a 25-year-long study of close to 1,500 Norwegians. Starting in 1987, when they were in their late teens and early 20s, participants filled out surveys that included questions on their recent pot use on five different occasions, into their 40s and....

Brad Pitt at work as Floyd in "True Romance".

Posted by JD Hull at 12:00 AM | Comments (0)

October 14, 2011

Sensitive Litigation Moment: Be There 24/7--or Give Walmart a Shot.

Lord Chief Justice Sir John ("Pompous") Popham, circa 1603

Lawyers aren't special. We're in a service business. We are not royalty. Get used to it. Rule 9: Be There for Clients 24/7. Returning telephone calls promptly and keeping your client "informed" is not client service. Color all that barely adequate. Get a new standard.

Posted by Holden Oliver (Kitzbühel Desk) at 11:59 PM | Comments (0)

August 04, 2011

Sensitive Litigation Moment #1: In Federal Courts, Use Declarations--not Affidavits.

.jpg)

Crystal, The Missing Oversexed Boozy Notary.

The rule is very handy here: your three oversexed resident notaries--Nadine, Crystal, and Little Sammy the Librarian--are in the office every day without fail, together with their goofy little notary kits, except the exact few days each year you need them to notarize something.

Not exciting. Just useful. In October of 1976, Congress passed a barely-noticed housekeeping addition to Title 28, the wide-ranging tome inside the U.S. Code governing federal courts, the Justice Department, jurisdiction, venue, procedure and, ultimately, virtually all types of evidence. 28 U.S.C. Section 1746 is curiously entitled "Unsworn declarations under penalty of perjury".

It allows a federal court affiant or witness to prepare and execute a "declaration"--in lieu of a conventional affidavit--and do that without appearing before a notary. Under Section 1746, the declaration has the same force and effect of a notarized affidavit. Read the 160 word provision--but in most cases it's simple. At a minimum, the witness at the conclusion of her statement needs to do this:

"I declare (or certify, verify, or state) under penalty of perjury that the foregoing is true and correct. Executed on (date). (Signature)”.

A "unsworn" declaration with the oath required by section 1746 can be used almost any time you need an affidavit, e.g., an affidavit supporting (or opposing) a summary judgment motion.

Many lawyers who practice in federal courts don't know about the existence of Section 1746, (probably because so many of us practice primarily in state courts, and we stick to comfortable state practices and folkways). I wouldn't have known about it either; a Justice Department lawyer clued me in on it 15 years ago.

Federal judges understand and accept it. It saves clients, witnesses and lawyers the time, cost and aggravation of getting client statements notarized. Your three notaries--Nadine, Crystal and Raphael the Librarian, together with their notary kits--are in the office like clockwork, except, of course, the very days you need to have them witness and notarize a document. So it's a useful and convenient provision. Not exciting--but it is one of the few efficient, and reliable, moments anyone sees in the trial process.

(from past posts)

Posted by JD Hull at 12:00 AM | Comments (0)

May 18, 2011

Sensitive Litigation Moment No. 15: Is "Professionalism" a Smokescreen for Bad Lawyering?

Professionalism--like good crops, the flag and motherhood--is indeed hard to criticize. It is also tough to define. Is it always good for clients? Can it even hurt them?

Weenie Alert: It's not about the lawyers anymore. In litigation, and in other contentious projects, does the practice of routinely and without question granting extensions, expanding deadlines, and saying "yes" to an adversary's requests for an accommodation really help clients? Or are such courtesies merely effete and provincial folkways that take the focus off the main event: solving problems for clients as expeditiously as possible? See "Professionalism Revisited: What About the Client?" in San Diego's The Daily Transcript of April 29, 2005. Has anything changed in five years?

.jpg)

Bar association meeting, San Diego. Pick any year.

Posted by JD Hull at 11:59 PM | Comments (2)

May 16, 2011

Sensitive Litigation Moment No. 14: Remember arbitration? How was that supposed to work, anyway?

Is there a way to stop feeding the monster? It's clear that both globally and in the U.S., arbitration and "ADR" have defeated the goals of Faster, Cheaper, Better. See, e.g., ABA Journal (April 2010) "International Arbitration Loses Its Grip". Any ideas on how to fix it? We need a system that works for clients--we already know it "works" for outside law firms--in business-to-business disputes. Why not have contract clauses that, regardless of the amount at stake, stipulate to one (1) panelist and require a decision in six (6) months?

Arbitration: Did it get as bad as the disease?

Posted by JD Hull at 11:23 PM | Comments (2)

May 06, 2011

Sensitive Litigation Moment No. 7: The Holy Surprise of Rule 56(d), Fed. R. Civ. P.

Disruptive as Hell: The "early-in-case" Rule 56 motion (note well-dressed Brit GC after taking a bullet here).

(d) When Facts Are Unavailable to the Nonmovant. If a nonmovant shows by affidavit or declaration that, for specified reasons, it cannot present facts essential to justify its opposition, the court may:

(1) defer considering the motion or deny it;

(2) allow time to obtain affidavits or declarations or to take discovery; or

(3) issue any other appropriate order.If a party opposing the motion shows by affidavit that, for specified reasons, it cannot present facts essential to justify its opposition, the court may:

Another Sensitive Litigation Moment. Trial lawyers know that Rule 56 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, or summary judgment, gives a litigant an opportunity to win on its claims or dispose of the opponent's claims relatively quickly and without trial. Accompanied by sworn affidavits, and most often discovery responses, a Rule 56 motion tries to show that there is no real dispute about key facts and that the movant is entitled to judgment under the law.

If the trial court grants it, the movant wins on those claims.

But what if a summary judgment motion is brought against your client--suddenly and out of the blue--and the local rules (or local folkways and practices) of the district court don't give you much time to develop and prepare an opposition. After all, Rule 56 lets a party who has brought a claim file for summary judgment after 20 days, and defendants can file "at any time".

In contentious, high stakes litigation, a quick summary judgment motion right after the commencement of a lawsuit can be extraordinarily disruptive--no matter how it is resolved by the district court. It will fluster even the most battle-hardened-been-there-seen-that GC or in-house counsel.

And it's an expensive little sideshow, too.

Subdivision (d) of Rule 56, "When Facts Are Unavailable to the Nonmovant", provides a safeguard against premature grants of SJ. Lots of good lawyers seem either to not know about--or to not use--subdivision (d) of Rule 56.

In short, you file your own motion and affidavit--there are weighty sanctions if you misuse the rule, so be careful--stating affidavits by persons with knowledge needed to oppose the motion are "not available", and stating why.

The district court can then (1) deny the request and make you oppose the motion, (2) refuse to grant the motion for SJ OR do what you really want it to do: (3) grant a continuance so that you can develop facts and, better yet, take depositions or conduct other discovery.

Granted, it's a delay-oriented rule, but if used correctly, Rule 56(d) can give you the breathing room and time you need to develop the client's case, and avoid the granting of summary judgment against it.

Note: An ATL reader caught our mistake in failing to recognize the renumbering and rewording of Rule 56(f) to 56(d) by the Advisory Committee. We appreciate it--and the correctly numbered subdivisions should now appear above. The crux of subdivision (f) was carried forward into (d), effective December 1, 2010. Thanks, sir. You are correct if pseudo-anonymous. But we were wrong.

Posted by JD Hull at 11:59 PM | Comments (2)